Will Big Law Go Hollywood?

In the constant calls for a more rapid evolution of the practice of law, the emphasis has been on the promotion of technology to supplement (or replace) legal tasks and the disengagement or outsourcing of routine matters to lower cost workers. But more central to the wider and immediate increase in the improved delivery of legal services is the development of more efficient legal employment models. Is the law firm partnership template still viable? What forms of organization can best provide legal services today? Is the growing “Hollywood Model” of ad hoc deployment of professionals applicable to law?

Legal work is not going away; the US Bureau of Labor and Statistics anticipates a 5% growth until 2024; comparable to other professional work (though the latest numbers show legal services employment as flat). The corporate merger boom in 2015 has continued into 2016, but it provides opportunities for only a select group of big law attorneys. Steadier legal work in North America and Europe is more a result of an increasing regulatory workplace affecting a wider group of companies (especially financial, health care, insurance, tech) where larger in-house teams, less acceptance of open-ended hourly billing, and a willingness to outsource, are decreasing the amount of work traditionally funneled to law firms.

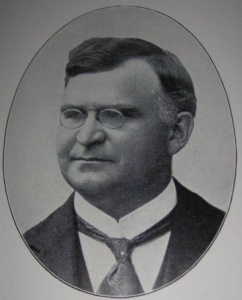

The law firm model itself predates the industrial revolution (England’s Thomson Snell & Passemore is nearly 450 years old) but the specific big law model, founded by Paul Cravath when Columbia Law drop-out Teddy Roosevelt assumed the US presidency, was an elegant staffing solution providing an efficient and stable professional collective of legal experts to advise growing corporate clients.

In those pre-LSAT days, Cravath hired the top academic students from a few prestigious law schools (many other law schools at the time did not require college qualification), intuiting that it is better to hire academically successful young men (the first female partner at Cravath wouldn’t be named until 1971) with no law firm or business experience, and therefore no bad habits. The long term partner-associate bond was the glue; not the particular matters worked on. The model proved successful and paralleled the escalator model of employment developing in the nascent company-centric world of their clients: an employee would work on an open-ended compact for the organization, advancing in pay and responsibility as the company expanded.

The Cravath model took it a Darwinian step further: this promising group of law firm graduates were hired and trained by the experienced attorney owners in a “tournament of lawyers” system that whittled down the number of apprentices, so that after a half dozen years only the best of these now-fully trained associates would be offered equity ownership as partners. The system worked but required that the clients subsidize the inexperienced associates’ pay, and that the partners take the time to train the associates.

It was an innovative model that transmitted knowledge of how to break down complex legal work to the committed but inexperienced associate. It permitted increasing delegation by the partner so that he could focus on the higher level strategy and growing needs of his current clients that would later benefit the younger associate. But it was the law firm bond of the associates and partners that was elevated over the profit making and taking of the partners.

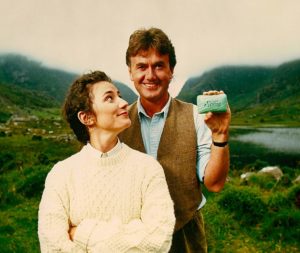

While working as a legal editor in Manhattan after practicing law in New England, I answered – on a dare from actor friends – a Backstage ad. “Irish Spring” was looking for a new spokesman. At that point, I had no real acting experience (other than in the courtroom), but a love of Shakespeare and a passable Munster accent (a semester at University College, Cork; summer work on my cousin’s Limerick farm) gave me confidence enough to bluff my way into an audition. And a second audition. And when the third and final came up, I passed it up, terrified that I’d be exposed, since I was from New Jersey, not Kerry, as my “enhanced” acting resume had it. (Later, when auditioning in Dublin for “The Commitments” – this time more plausibly as an American journalist— I learned that Procter & Gamble couldn’t have cared less where I was actually from – the “Lucky Charms” leprechaun was voiced for fifty years by Staten Island native Arthur Anderson; an actor of completely unIrish roots).

But here’s the point. To do the commercial, Procter & Gamble’s ad agency, Young & Rubicam, wrote the script, then, once approved, hired an independent producer and director, who assembled the global team of professionals to make the commercial. These individuals – casting director; locations manager; cinematographer; sound engineer; editor; even craft services manager – were skilled independent workers coming together to make that commercial. This is the “Hollywood Model”: the most efficient way to assemble talented, creative professional workers to produce defined-term projects. It wasn’t always that way – in Hollywood’s four decade Golden Age that lasted though the 1960s, the studios functioned as one-shop filmmaking entities (similar to the Cravath model), with artists and craftspeople employed and apprenticed under long-term employment contracts (and, until antitrust concerns drew the curtain on the studio’s vertical integration, the studios also controlled the distribution and exhibition of their films).

Today’s project-based Hollywood model differs from the short-term, one person contractor “gig” model (think “Uber”) in complexity and wider ranging applicability, and it’s become a popular alternative to the century-dominant corporate model. In the Hollywood model professionals are hired strictly for a project with a defined end date, and it is being used in a growing number of nimble ventures that have creative components, including music, restaurant design and fashion. In the friction-free economy that supports the Hollywood model, much less capital is needed as workers are hired on an as-needed basis.

Could the Hollywood model offer a solution for more efficient deployment of legal services? It’s happening already. In the pre-recession and pre-predictive coding eighties and nineties, contract attorneys were the dirty little secret that law firms and corporate law departments deployed, generally vetted and hired by third party agencies for short time document reviews or research projects, but housed in relatively plush firm or corporate settings and integrated with the client, mitigating the severely lessened pay they received compared to their law school classmates who were hired as associates at the same outside counsel firm or the inhouse associates.

But with the recession came a surfeit of unemployed attorneys willing to do any work designated in name if not by pay “legal”. Hourly rates spiraled down; the increasingly commoditized contract attorneys were separately housed in cheaper locations, segregated from the corporate law and outside counsel leaders as well as from the client’s unique culture. The outsourced attorneys went from offsite to offshore in many cases, further depressing pay, and further depressing recent law school grads forced to take document review contract jobs for less pay. It became not only less efficient but soul draining.

Since Judge Peck’s approval of predictive coding three years ago, the bottom has dropped out for the need for JDs for document review work. The legal staffing agencies that survived are deploying higher level legal specialists – including experienced attorneys – to work with the clients onsite, though such attorneys must be still be closely supervised under ABA Model Rules 5.1(b) and 5.3(b), limiting efficiency for in-house counsel.

Another evolving efficiency in legal staffing is the growing use of litigation funding. For law firms, capital is raised from partners to finance firm investments, with the amounts invested based on projected annual income (contributions usually at 20-25%), and supplemented by bank lines of credit. But since the Dewey collapse, firms are seeking a higher percentage of partner contribution rather than face possible bank defaults, challenging capital needs.

For law firms, litigation funding provides assurance of capital flow and coverage of fixed costs, without giving up all of the firm’s contingency fee. Law firms can also offer a client the option of funding via a respected third party, permitting more alternative fee arrangements and greater likelihood of asserting rights via litigation that they would otherwise decline to pursue due to high costs and risks; a win for the client and outside counsel. The corporate client can also benefit directly from litigation funding, knowing that it can bring an affirmative action without blowing up the legal department budget, and even contributing to the company profits. It’s providing elements of the Hollywood model in allowing a dedicated professional funding entity to allocate capital and assist with risk management, reducing the capital contributions of the law firm partners as well as those of the corporate client.

ABA Rule 5.4 prohibits non-lawyer sharing of profits, and prohibits law firm incorporation where outside investors could provide much needed capital. The conservatism and self-protection mechanisms of lawyers have held back on the obvious need for more efficient business models. Law firms are businesses; the ABA will be forced to recognize that, and the ethical obligations of an incorporated business of lawyers practicing law can be enforced by retaining individual lawyer obligations while permitting incorporation (particularly if the directors of the corporation are the actual lawyers).

The Hollywood model offers a future for the provision of legal services. The ideal model will work as Hollywood truly works: the client is analogous to the studio, a group of traditionally employed professionals, who, when faced with a legal issue that cannot be handled in-house, will seek the independent judgment and assistance of a particularly suited outside counsel. That firm, akin to the ad agency (for commercial) or producer/director (film), should deploy and supervise the team needed, and they shouldn’t be all lawyers, but skilled in the task assigned.

The increasing ability of businesses to more timely quantify and track data and business needs (including legal) is allowing more quantification of discrete legal tasks, permitting a wider range of work assignments with a better projection of costs and more demanding deliverables. Although the business client is more likely to consolidate more work with a dwindling number of outside law firms (and favor those most responsive and efficient –even if not big law), the quantized legal assignment allows greater flexibility in deciding who can carry out the task instead of defaulting to outside or inside counsel, and can also allow greater delegation by the law firm to the professional best suited to the task.

On the supply side, talented young lawyers are demanding a work-life balance and are reluctant to commit to the half-dozen years of subservience and unlikely odds of winning partnership in the tournament of lawyers system, providing further catalyst for more flexible employment arrangements. Law schools will also have to include that experiential training once provided by the Cravath model, but on an expedited schedule so that graduates can be more productive upon graduation. Mentorship of associates is dying. In fact, the “virtual” and growing law firm FisherBroyles is a reverse of Cravath- a firm of experienced attorneys connected by technology that has forgone the mentorship model of the traditional law firm, and thus delivering services at better prices without the overhead and training costs.

In an ironic footnote to this discussion, there will soon be a literal integration of Paul Cravath with the Hollywood model. Eddie Redmayne will be playing the lawyer (despite being five inches shorter and five stone lighter) in the big budget adaptation of Graham Moore’s new historical thriller “The Last Days of Night.” It will not, however, focus on Cravath’s law firm staffing innovation, but on his epic defense as a young attorney of Westinghouse versus litigious Edison over the invention of the light bulb. It’s a role I would have loved to audition for (and wouldn’t have backed out from!), but the Hollywood model needs a star to ensure a presentable box office take (especially for a big budget historical drama), not an actual lawyer–actor who would neatly fit Cravath’s bespoke tweed suits. Moreover, With Moore & Redmayne’s skill (and studio commitment), Paul Cravath will be getting his long deserved legal fame via the Hollywood model, at the same time that his century old staffing model declines.

(an edited version of this article appeared in ABA Law Practice Today, December 2016)