Socratic AI: Using Artificial Intelligence to Accelerate Lawyer Learning

“I cannot teach anybody anything. I can only make them think.”

attributed to Socrates, circa 390 B.C.

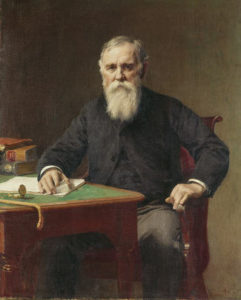

“Law is a science, and… all the available materials of that science are contained in printed books….”

Prof. Christopher C. Langdell

Speech at Harvard University, 1887

Discussions to date on artificial intelligence and law commonly seek the diminishing demarcation between the human-only part of lawyering (multi-disciplinary integration, especially regarding strategy; ‘reading” the client; emotional intelligence) and those lawyering skills more efficiently accomplished by machines (legal pattern recognition research for document and contract review). But the more meaningful inquiries have not been asked: will human-AI collaboration advance the lawyer’s counseling? Can the AI system help the human lawyer overcome bias and produce better decision-making?

Traditional legal training is often criticized as inadequately preparing law students for the increasingly tech and data integrated counseling required in today and tomorrow’s markets. Yet there was a time when the most advanced and truly disruptive professional teaching method emerged from a law school.

Christopher Columbus Langdell initiated both the case method and the Socratic method of teaching law in his Harvard Law class one hundred and fifty years ago. Langdell’s goal was to induce the legal reasoning of actual cases through a series of specific questions (the Socratic method) that would expose the biases and preconceptions of the law student. In a common law system, this original source-first focus properly centralized the primacy of case law study over lecturing about a generalized legal subject, allowing students to think more objectively and deepen case-specific legal reasoning. The case study system, employed with the Socratic method, forces the student to challenge their own inferences to foster more objective, less biased legal decision-making. It was a revolutionary approach to teaching, and became the standard method of law school teaching and greatly influenced graduate school education as well.

The explosion of artificial intelligence in our current society is due in large part to the success of the “deep learning” model. This type of AI, a subset of machine learning, is modeled after the human brain. Deep learning AI employs layers of hierarchal networks, where higher level layers work off lower levels to learn complex functions directly from the date inputted, with very little human tinkering.

Lawyers are notoriously scared of math, but it’s essential to accept how the independence and precision of mathematics can make them better lawyers in today’s data-driven world. Attorneys must understand that the advanced artificial intelligence process underlying legal research in a deep learning system transforms words into numbers; more specifically words are mapped into vectors. This word embedding into vectors captures the degree of similarity of words across the vector space. It’s not a simple, static, one-to-one mapping of a word to a number, but a more complex and accurate representation of the many facets of that word as used in actual context. As humans we use language as an imperfect signpost for more complex thought; but deep learning AI, with its greater (if narrow) cognitive power doesn’t have human language biases (apart from implicit in that corpus of used words) or limitations in finding the clear mathematical similarities. The deep-learning system can guide the lawyer to otherwise untapped legal reasoning, enhancing the human-only legal advising and making the humans better lawyers.

When the human lawyer engages with a dynamic, artificially intelligent, less-biased system that establishes legal connections through a more thorough exploration of paths – including some that a human may not yet have found – then the lawyer engaging with it will have stronger options in coming up with legal answers. The lawyer should then understand that legal area in a deeper way by “seeing” more connections. Although these advanced AI interactions differ from the student teacher dialogue of the Socratic method, the result in large part is the same: an accelerated understanding of more complex, comprehensive, and clearer legal options, with less decisionmaker bias, providing a stronger foundation for better lawyering. The system can illuminate options and facilitate a broader and deeper understanding of the legal issue.

The perverse pride of lawyers of their math phobia runs deep, especially when numbers are applied to law. Only a few months ago America’s top jurist – Chief Justice Roberts – trashed the use of math in the gerrymandering challenge in Gill v. Whitford as “sociological gobledygook”. But data science is an essential tool to elicit fact-grounded decisions that will make better lawyers, jurists, and law.

Last year, Google’s deep learning artificial intelligence system Alpha Go Zero did something extraordinary. In 40 days it trained itself to master the Chinese board game Go, without human intervention or training. It played millions of games against itself as it steadily increased proficiency, beating what any human could do, then beating every other machine. The only human input was the rules of the game, and the “loss function” programming which essentially determined whether each move tried would increase its chance of winning. On its own (though over the course of millions of games played by it, exploring and advancing proficiency) it developed (dare we say “evolved”?) strategies and skills that humans had come up commutatively but over hundreds of years. Not only did it independently learn the human strategies, but more importantly, came up with new and better ways to win. Human players now use Alpha Go Zero strategies as an accepted part of the game.

Alpha Go Zero teaches us that the cognitive power of an artificially intelligent system can surpass human reasoning. Note this doesn’t make it “smarter” than humans. But in the case of Alpha Go Zero, the system has advanced the human’s play to a higher level as humans now commonly use the higher-level strategies discovered by it; raising the human standard of strategy. Lawyers aren’t playing a game, but are indeed looking for connections in the common law cases or corpus of documents; connections that can be clarified by translating them into fluid, but less biased algorithms. The fear of AI as job executioner should be replaced by the acceptance of it as a kind of mentor to help lawyers find and understand legal connections. The Socratic method teaches students by exposing bias to discern legal truths; the AI system is similarly exposing truths in searching through that manmade corpus of the common law, making it more open as well as more digestible.

Any discussion of advanced AI for legal decision-making needs to answer the ethical obligations of the attorney using the tool. As the AI systems contemplated here are not self-initiating but very much tools of the attorney, we needn’t address unauthorized practice of law concerns. Instead, the Scylla and Charybdis of the obligations require navigating between the attorney’s nondelegable requirement to supervise nonlawyer assistants (ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct 5.1 and 5.3) and the counterbalancing requirement of competent representation (Model Rule 1.1) . This competency obligation includes – via Comment [8], adopted in a majority of jurisdictions – keeping “abreast of changes in the law and its practice, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology…”

As advanced, safe, and dynamic artificially intelligence systems become more widespread and efficient in accelerating core, human-only legal reasoning, the obligation of competency grows to a point where non-use becomes ethically questionable. The supervisory duty in using AI does not require complex math fluency by the attorney, but still it requires the ability to understand how the system comes up with its answers, and if necessary may require third party consultants or data scientists to assist the lawyer in opening that “black box” in a defensible manner. Also, if the AI is used in examining data beyond case law and statutes, the lawyers must also consider client data confidentiality requirements.

When Professor Langdell disrupted the standard professional teaching methods for law by introducing his Socratic method, he was seeking a more scientifically-based, rigorous means of directing his students to think like lawyers; like good lawyers, with less bias and sharper observational awareness to advocate in a world challenged by the industrial revolution. It is time for lawyers today to recognize the tool of advanced artificial intelligence in much the same way; a means of lessening bias and finding deeper connections faster, making us better lawyers in an increasingly more complex, technologically-integrated world.

(an edited version of this article appeared in ABA Law Practice Today, January 2017)